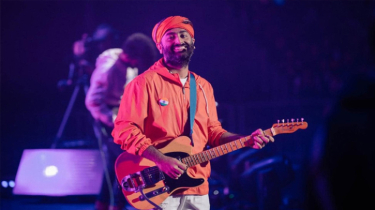

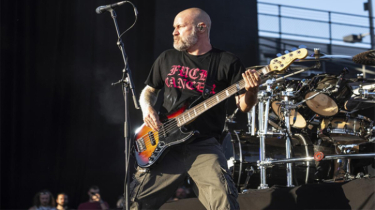

After Zubeen Garg’s Death, a 38,000-Song Legacy Triggers a Rights Reckoning

Published : 23:39, 27 October 2025

Assam’s most prolific modern vocalist, Zubeen Garg (1972–2025), died in mid-September in Singapore following a scuba-diving accident.

In the weeks since, an unusually large and fragmented catalogue widely reported at more than 38,000 recordings across Assamese, Hindi, Bengali, and other languages has catalysed a public dispute over who owns, controls, and can monetise his repertoire.

The question traverses Indian music-industry contracts from the cassette era to today’s streaming ecosystems, as well as succession law and artists’ moral rights.

Following allegations and speculation online, Garg’s longtime manager, Siddhartha Sharma, released a detailed statement asserting that the vast majority of the singer’s recorded works are contractually owned by music labels and film producers that commissioned the sessions.

He further indicated that Garg was typically paid one-time recording fees rather than granted ongoing royalty participation, standard practice in earlier decades for playback and non-film releases, while a smaller subset of later works was routed through an entity founded by the singer (Zubeen Garg Music LLP).

Sharma also said the LLP equity would pass to the family in probate. Parallel to these clarifications, Assam authorities have been conducting inquiries related to the circumstances surrounding the death; the manager has said he is cooperating fully.

The ownership debate has been amplified by the discovery and curation of large private archives. A prominent collector in Assam has publicly opened an extensive repository claimed to include more than 38,000 tracks by Garg, some of them rare or otherwise unavailable, along with associated ephemera.

While such collections play an important role in preservation, they do not transfer copyright or neighbouring rights; licensing for public communication, reproduction, or commercial distribution would still depend on the underlying contractual chain of title.

From an industry-law perspective, the case illustrates several tensions.

First, historic “work-for-hire” or producer-assignee contracts often left artists with minimal royalty rights, particularly outside cinema soundtracks’ lead singles. Second, the transition from physical to digital distribution magnified the value of deep catalogues while exposing gaps in metadata, performer credits, and royalty routing.

Third, Indian law recognises authors’ moral rights (including the right of attribution and integrity), which persist independent of economic rights and can be asserted by estates.

Practically, however, enforcing claims over a multilingual, multi-label corpus of this size requires cooperation among heirs, labels, publishers, collecting societies, and platforms to standardise metadata, clarify ownership splits, and operationalise payments.

In the near term, stakeholders face three immediate tasks. (1) Estate administration: confirm legal heirs and the status of the LLP interests, and appoint professional counsel to interface with labels and platforms.

(2) Rights mapping and preservation: inventory masters and compositions, reconcile label contracts, and digitise archival assets with proper provenance documentation. (3) Monetisation and access: negotiate catalogue-wide agreements (or “framework licences”) covering streaming, compilations, reissues, and synchronisation, with transparent reporting to beneficiaries.

For fans and cultural institutions, formal partnerships with rights-holders can enable public exhibitions, curated playlists, and scholarly access while respecting intellectual-property constraints.

However, the legal mechanics unfold, Garg’s legacy is secure on artistic grounds: a three-decade career spanning popular cinema, independent albums, regional folk idioms, and live performance.

The present reckoning sparked by a singularly vast discography may yet set a precedent for how South Asian music estates document, license, and share culturally important bodies of work in the streaming age.

Sources: Hindustan Times, Times of India, India Today, Gulf News, India Times

BD/AN